If you Google “end of Internet”, you will actually find many pages that purport to the THE end: the last page of the Internet. Enjoy the fun to be had on this humourous page, but I’m partial to the page Bill Weinman posted in 2006: In a muted grey-on-grey colour scheme, it simply says: “You have reached the end of the Internet. We hope you have enjoyed your experience. Now go outside and play.”

Of course, there is no end to the Internet. The really interesting story is about the beginning of the Internet — and that’s why I mention here Maria Popova’s “brain pickings” article on 100 Diagrams That Changed The World, a 2012 book by Scott Christianson.

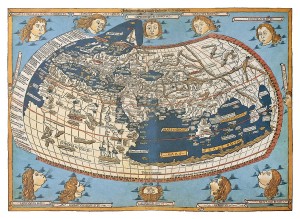

Christianson’s goal, as stated in the Amazon.uk blurb, is to present “a fascinating collection of the most significant plans, sketches, drawings, and illustrations that have influenced and shaped the way we think about the world. From primitive cave paintings to Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man to the complicated DNA helix drawn by Crick and Watson to the innovation of the iPod, they chart dramatic breakthroughs in our understanding of the world and its history. Arranged chronologically, each diagram is accompanied by informative text that makes even the most scientific breakthrough accessible to all.”

In Popova’s overview, she underscores the real achievement of this book: “But most noteworthy of all is the way in which these diagrams bespeak an essential part of culture — the awareness that everything builds on what came before, that creativity is combinatorial, and that the most radical innovations harness the cross-pollination of disciplines.”

Yes! After reading Popova, it dawned on me that the Rosetta Stone (196 BC), the Heliocentric Universe of Nicolaus Copernicus (1543), the emoticons of Puck magazine in 1881, Tim Berners-Lee’s “mesh” information system, start of the World Wide Web — and many other diagrammed representations of the way things are (or could be) are, in effect, great examples of nextsensing. In its own way, one could see this book as an interesting way to show how humans, across time, have actually been very good at making sense of things to advance understanding by using graphic artistry. I submit to you that the 100 diagrammes in this book could quite possibly be seen as a graphic history of finding next.

We’ve all heard the picture-worth-a-thousand-words cliché. When I work with some groups trying to discover their organisation’s next, I often find that the power of visions converted into images is often greater than the best-written business plan — at least in terms of igniting some common passion around the discussion table.

To be sure, Claudius Ptolemy way back in 150 A.D. had an even bigger job in proposing to people what the entire world looked like as a map. And, in terms of being both accurate and to scale, Ptolemy was wrong. Yet, where would any of us be if he had not put forth his view of the next best way to circumnavigate the globe?

Use words or draw pictures, either way the job of finding one’s next is an exciting journey fraught with misconceptions, mistakes and misunderstandings. But, as a testable and doable prospective opportunity evolves, one quickly sees that all the zigging and zagging that came before was quite possibly invaluable.

Maria Popova is spot on when she asserts the importance of placing a high value on “the awareness that everything builds on what came before, that creativity is combinatorial, and that the most radical innovations harness the cross-pollination of disciplines.”