The New Language of Entrepreneurs

I first met Dimo Dimov (@dpdimov) in 2004, as he was finishing his PhD in Entrepreneurship at London Business School. That same year Dimo [link] joined me as a professor in the Entrepreneurship Department at IE Business School in Madrid, Spain [link].

During our time together at IE, we have collaborated often in working with MBA students or on courses tied to the subject of entrepreneurship. He is also one of our founding Nextsensors [link].

Dimo and I have a number of points of connection on a personal level:

- Dimo is from Bulgaria, and my family immigrated to the US from Romania. I have studied in Budapest, and my master’s thesis focussed on the socio-economic transition of the central and eastern European countries. Dimo once served as the CFO of the Budapest Marriott, and we often revisit stories about life in Budapest and our shared affection for the city.

- Dimo’s background combined working as a corporate manager as well as his training as a scholar. Same here. This has served us well in helping our students to connecting the dots between scholarship and the practice of entrepreneurial management.

- Like me, Dimo is a global citizen, having lived in Hungary, the UK, the US, and Spain — as well as his native Bulgaria.

No matter where we might be, we always stayed in touch. I have always found his research interesting, his ideas provocative, and his intentions admirable. After I read his 2017 book The Reflective Entrepreneur [linkUK] [linkUS], we discussed our mutual research and approaches to entrepreneurship. Just as I did, he immediately saw the connections. So, we have been working closely ever since.

We now are developing a shared vision for a teaching philosophy with assessment and instructional tools for educators and students. After a recent appearance together in London at a corporate seminar, I talked with Dimo about his book and how it is helping to shape a new relationship with The Nextsensing Project.

Pistrui: Early in the book, this sentence grabbed me: “People come up with ideas but, as entrepreneurs, they pursue opportunities.” What made you think of that?

Dimov: There is often a sense that ideas do all the work, that once we have a good idea, the rest is history. But ideas are static, they do not engage with reality, they are infinitely perfectible. It is the drive to make them real that matters, the pull of the future they represent. It is the combination of an idea and its pursuit that captures the essence of entrepreneurship. What makes you an entrepreneur is not whether you have ideas but whether you do something about them.

Pistrui: You refer to people with new ideas as either geniuses or lunatics. Should this inspire or intimidate a budding entrepreneur?

Dimov: Ideas come from hunches, intuitions, gut feelings; and it is impossible to communicate these to another person. We can look at the same situation but “see” different things. This lies at the bottom of the genius vs lunatic tension of the entrepreneurial journey — that our ideas are bound to be met by scepticism by others. If the scepticism is not there, this is perhaps a sign that our ideas are not groundbreaking enough. Rather than being intimidating to budding entrepreneurs, this should bring them comfort that pushback and rejection are normal parts of the process.

Pistrui: How important is “luck” in being a successful entrepreneur? For example, were Richard Branson and Steve Jobs more lucky than brilliant?

Dimov: When we think of luck as all the things beyond our control that have gone in our favour, then luck is essential. But so is, of course, skill or brilliance. It is not a question of whether one is more important than the other, or whether one should be labelled lucky or brilliant.

The best way to think of this is as SUCCESS = SKILL x LUCK.

The multiplication effect means that if skill or luck are missing, then success will not come about. We can control our skill by practice and learning, but we cannot control our luck. Yet, if we think of our overall luck as the sum of all the tries we make, then we get to the familiar saying “the harder I try, the luckier I get.”

Pistrui: You talk about books and entrepreneurial ventures having some characteristics in common. How so?

Dimov: For both books and entrepreneurial ventures, ultimate success is a verdict of the marketplace. Behind that verdict is the socially interdependent ways in which consumers make their choices: what I choose depends on what my friends choose, and vice versa. We are influenced by the preferences of others; and the more popular something is, the more likely we are to choose it over competing offerings.

Just think of the star ratings that are now an essential part of purchase decisions, such as those on Amazon.com. The implication of so many people sharing their buying preferences is that the distribution of success is not normal (bell-shaped) but has a long-tail. The vast majority of books sell little; most ventures operate at a small, lifestyle scale; but there are some huge successes (bestsellers, Unicorns).

Pistrui: You note that entrepreneurs face both an exterior journey (the company, project, and so on) and an interior (mental) journey. Aren’t all entrepreneurs, at the core, alike — cut from the same human cloth? And, later, you talk about “managing internal pressures”. Sounds like an entrepreneur can fail both by how he/she thinks and how he/she acts. True?

Dimov: Most food dishes are made of the same basic ingredients, but think of the diversity of dishes out there. Yes, we are all human at our core, but our personalities, education, and life experiences create much diversity in what we want and how we respond to the same situation.

Over time people develop internal gatekeepers within themselves on how to think and act, judgements of what is right or appropriate. But these are self-imposed. They create blind spots in terms of what someone believes can be done or is possible. How we think and act can lead to failure in the sense that it prevents us from exploring the full space for development of our ideas.

Pistrui: What are “wicked problems”?

Dimov: The entrepreneurial task is a complex problem, with many parts that pull our solutions in different directions. The wickedness arises from the fact that solving one part can worsen another. Thus, an entrepreneur is after something that needs to be desirable in the market, technologically feasible, and financially viable. She or he may know what customers want but also realise that this is not feasible or too expensive to make. Any compromise on the latter may make it no longer desirable. What customers need or want and what an entrepreneur can offer may be different things. Aligning them puts entrepreneurs through such a wicked, iterative process.

Pistrui: In our new work together, what excites you the most?

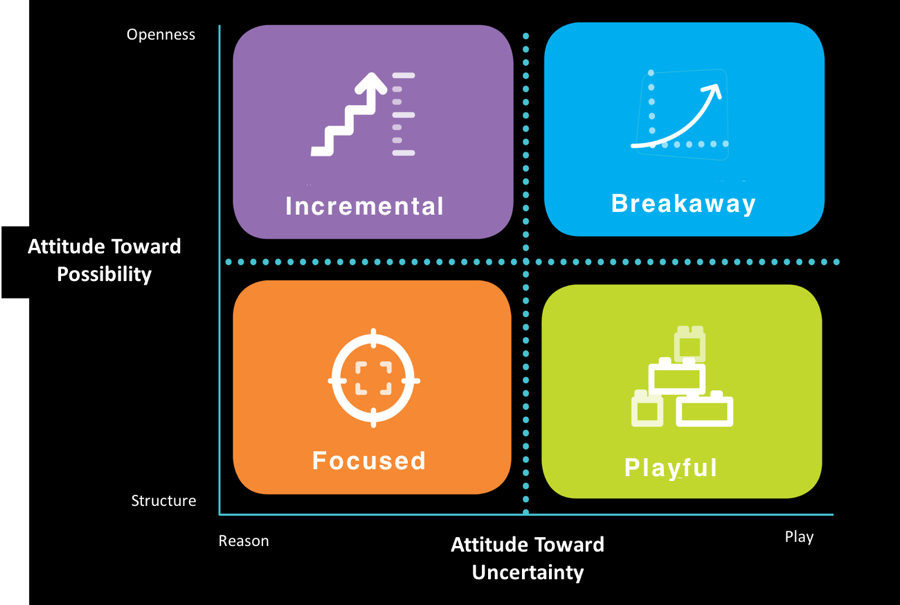

Dimov: Our work enables us to make the question “Are you an entrepreneur?” moot. Instead, we recognise that it is more relevant to ask “What type of an entrepreneur are you?”

This question makes it obvious that it is not enough for an organisation to want to be more entrepreneurial. There needs to be a specific direction for development, a roadmap that recognises where they are and where they might want to go.

The new matrix framework that we are designing as both a concept and as an assessment tool enables people to find their starting point as an entrepreneur. It’s no longer a binary matter: that you are or are not an entrepreneur. Our new approach makes entrepreneurship like a language of moves to be mastered and used in different combinations in different situations. For anyone to master the language, they need to recognise that they have grown accustomed to only some of them. This in turns opens them up to what they could do differently. This is a source of boundless excitement for me.

Joseph Pistrui (@nextsensing) is Professor of Entrepreneurial Management at IE Business School in Madrid. He also leads the global Nextsensing Project, which he founded in 2012.

Joseph Pistrui (@nextsensing) is Professor of Entrepreneurial Management at IE Business School in Madrid. He also leads the global Nextsensing Project, which he founded in 2012.