While Gutenberg’s paper-and-ink process is far from dead, the Internet dominates written and graphic communication today. So a recent post by Noah Kagan (@noahkagan) was most interesting. The headline: “Why Content Goes Viral: What Analyzing 100 Million Articles Taught Us.” [link] Here’s his introduction:

A few weeks ago someone sent me a link to the BuzzSumo website [link]. It is a gold mine of data regarding what content is the most shared across any topic. Cha-Ching. So I reached out to the company to help understand what the main ingredients for insanely shareable content are. You may have seen some articles related to this but this is backed by pure data. Use their knowledge with caution.

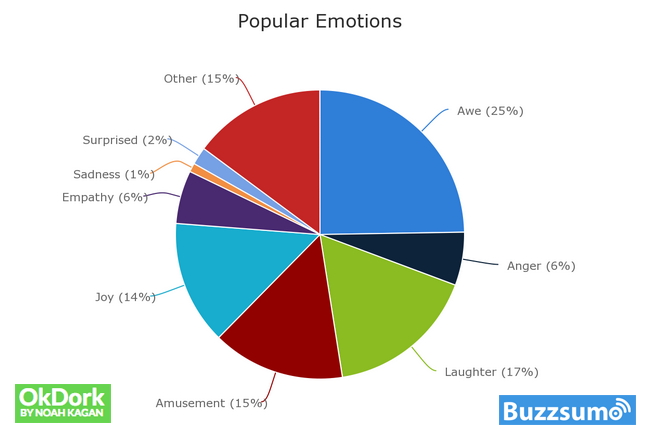

What Kagan did was to invite Henley Wing (@HenleyWing), the founder of Buzzsomo.com, to report on that analysis of 100 million articles — and report he did, with 10 major learnings that cover how the inclusion of images help readership, how “awe, laughter, amusement” provokes sharing, and how trust is essential to the spread of ideas and facts on the Internet. There’s more, of course, and you should definitely check this out if you have any interest in what makes information go “viral”. Wing says Buzzsomo’s analysis was driven by some critical questions (and one given):

- What types of emotions did the most popular articles invoke?

- What type of posts typically receive a lot of shares? (lists? infographics?)

- Did readers love to share short form or long form content? What’s the ideal length?

- Does trust play a major role on whether someone will share an article?

- What’s the effect of having just one image in a post vs no images?

- What’s the effect of having just one influencer sharing your article vs 0?

- How do we make people share our post days and even weeks after it’s been published?

- What’s the best day of the week to publish an article?

The given? Says Wing: “Of course, the prerequisite to getting your content shared widely is to write compelling content.”

Check Noah Kagan’s site for great information, which is accompanied by great charts. For example, on the subject of how emotional tugs can affect whether something goes viral, Kagan’s site [OKDork.com] posted this fascinating chart:

While absorbing all this, I paused to think about the entire phenomenon of Internet content going viral. When I asked this question today: “How many things go viral on the internet?”, Google responded with 150,000,000 hits. Needless to say, a lot of items go viral presumably every day. Is that a positive for the Internet? Does the fact that something goes viral indicate that more people are benefitting from such faster-than-the-speed-of-Gutenberg communication? In short, is viral healthy?

Of course, I look at the world through a nextsensing pair of glasses. My thoughts on all this? When it comes to meaning and sensemaking, language indeed matters. And so I suggest we ask an important question when something goes viral: is it merely “trendy” or is it potentially “trendsetting”?

When something is merely trendy, it is more of a present-tense follow on (even pile on!) effect to something that has quite possibly already changed. It’s being zip-zapped electronically by and to the masses, to guarantee that as many friends and contacts don’t miss out on something that seems “hot” in an immediate sense. Surely, you have received e-mails or direct-message tweets with subject headers such as “You Gotta Watch This!” or “Stop! Catch This Now” or some such. And everyone who picks up on the suggestions — and spreads them further — thus becomes a participant in the viral phenomenon.

For examples, you can go “simply zesty” for a nice assortment of viral videos: “Top ten examples of viral success through Youtube” [link].

Those who are more interested in trendsetting rather than simply trendy should consider that, when something is really the start of a major, long-term trend, it means that the virality of the information is still in the future. That is, something that is trendsetting is a future-tense concept and reflects the growing influence of a new or emergent trend on the horizon that may not yet be fully taken root. It is not difficult to calibrate the impact on an organisation between something that is trendy and something that is trendsetting.

For example, last October MIT Technology Review posted “The Top Five Trend-Setting Cities on Twitter” [link]. Data like this seems much more worthy of using for examination of what the future holds for housing, fashion, sports, or whatever your interest might be. I’ll let you read the post, but it tells you why you might not want your R&D team to be digging into what’s happening in Albuquerque or Omaha if you’re trying to build your business around future trends.

So when something goes viral, we should be looking for their trendsetting capacities so as not to be confused by circumstances in which the masses are madly sharing something curious or fun rather than starting something profoundly new.