Computers have invaded the modern classroom. Is that good?

Our use of computers (especially laptops), smartphones and tablets is indeed an important new behaviour that likely will have lasting implications in the field of education. From younger children who play learning games in their elementary studies to collegians who seem permanently attached to the e-world via some device, the computer chip has made many things possible that never used to be.

For example (and I’ll focus mainly on the college level for this post), students can now type lecture notes much faster than they could with paper and pen. They can also record some classroom activity, to review and digest at a later time. They can also use class time to do e-mails, read social media posts, or watch a movie. Since the professor is looking at them only partially (their raised laptop lids block the prof’s view), it would be hard to enforce any announced code of student conduct, if one even exists.

Dan Rockmore is a professor in the computer science area of Dartmouth College (@Dartmouth). He’s been getting a great deal of attention since his 06 June post in The New Yorker [link] titled “The Case for Banning Laptops in the Classroom.” It’s well worth everyone’s time to read his article, which provides both points of view on whether computers are helping to create smarter students or just more tech-savvy students.

Rockmore generally comes down on banning computers in classes: “Our ‘digital assistants’ are platforms for play and socializing; it makes sense, then, that we would approach those devices as game and chat machines, rather than as learning portals.” He also adds, “We’re not all that far along in understanding how learning, teaching, and technology interact in the classroom.”

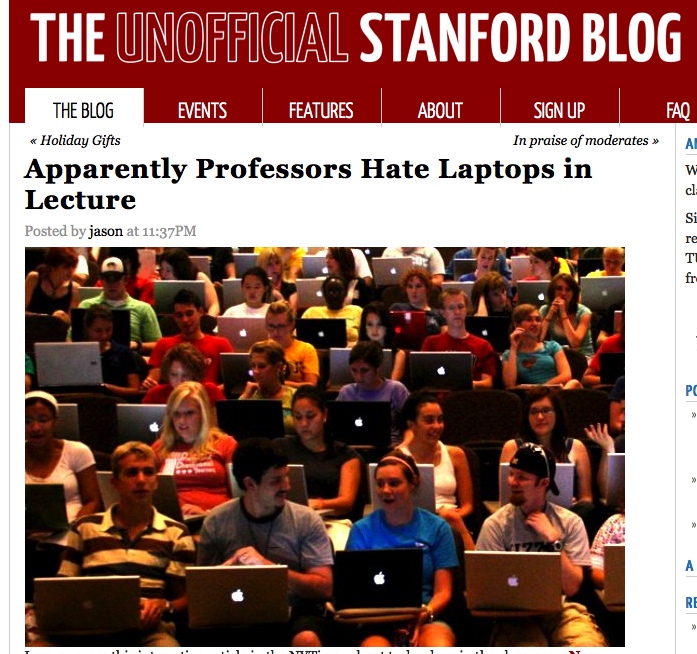

The subject has been a hot one for some time. The Unofficial Stanford Blog, last December, carried the story [link] and invited reader comments to this headline: “Apparently Professors Hate Laptops in Lecture.” Written with a student point of view, the short arricle pondered how a student doing e-mails in class is any different than the student 25 years ago who doodled on his spiral-bound notebook all class.

As we get deeper and deeper into embedding technology into our daily behaviour set, it raises serious questions — some good and others not so much — about the impact of technology on ourselves, our work and how we learn, grow and develop.

As a professor (although there is little “professing” these days), this issue is not only a theoretical one, it is a tangible day-by-day concern. Here’s what I love about having computers at the students’ fingertips: (1) access to instant information, (b) ability to request students to do instant research, (3) ability to provide students time to dig deeper into a concept without any delays. I’d also say that many a class session has been enlivened by some online discovery by a student that is new and vital information to everyone in the class, myself included.

But there is no denying the downside to computers: (1) a much shorter attention span, (2) my need to compete for the students’ attention (and I am competing with the world!), (3) the implicit disrespect it has for others in the room (and not just me, but also peers) when one student is self-absorbed in something “that just cannot wait” or is “more important” than the prevailing class discussion.

A true NextSensor would, most likely, favour that we study all this much more carefully before issuing a ban on tools that are, without doubt, powerful. Can anyone fairly judge technology in the classroom before we fully understand it?

Three truths I would posit at this point.

First, we have all become used to tapping into the world’s knowledge base anytime and anywhere. That means we are not only dealing with new technology, we are dealing with new norms.

Second, all of us seem to now ahhere to a “can’t wait” code. Whatever information one seeks, if you cannot find it instantly, often leads to abandonment. That is, people may seek a certain point of knowledge; but, if not accessed speedily, they may easily allow themselves to accept some tangent of what they were looking for or abandon the search and just move onto some other matter of interest. In the past, researchers had prodigious patience. That increasingly seems to be a lost art.

Lastly, we need to become “captains of our ship” and make good choices about how, when and why we are using new technologies — just as we have historically done with other technologies (electricity, automobiles, radios-and-televisions). As technology becomes more powerful and more present in our lives, we must ask whether we are driving it, or if it is driving us.